The Celts are said to have originated in central Europe 14,000 years ago in modern-day Austria (Hallstatt), migrating westward from the seventh century BC onwards. Today, most people of Celtic origin are found in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, England, France, and Spain, as well as in the immigrant populations of the U. S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, who left their homelands during the expansion of the British Empire.

The C is hard as in [K]elt, although it has been transformed in the U. S. to a softer sound as in [S]elt, hence the basketball team the Boston Celtics or [S]eltics. That doesn’t make them any less ferocious.

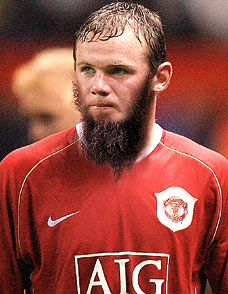

What characterizes a Celt? I always thought a stocky, broad-shouldered, warrior type, and judging from the best rugby teams which all come from Celtic (or Celtic-stocked) countries the description seems apt. Fortunately, warriors no longer die on the battlefield in the most war-like of sports. Think Wayne Rooney or Brendon Gleeson with a beard. For a softer look, think Lindsay Lohan or Cheryl Cole.

But not all are red and proud. In The Celts in Wales, Sarah Woodbury describes two types: 1) stocky and dark and 2) tall and blonde, which may distinguish the more insular Celts of Britain and Ireland, who were pushed north into Scotland and Ireland and west into Wales and Cornwall by the Romans, and their continental counterparts in France and Spain, whose genetic makeup is more diverse after centuries of intermingling. Pockets of Celtic blood are found on the continent, most notably in western France (Brittany) and northern Spain (Galicia and Asturias).

Genetic tests have shown common Celtic bloodlines and DNA across national boundaries. As Marie McKeown notes, “the latest research into both British and Irish DNA suggests that people on the two islands have much genetically in common. Males in both islands have a strong predominance of Haplogroup 1 gene, meaning that most of us … are descended from the same Spanish stone age settlers.” That helps explain the Spanish connection, mostly ignored when one thinks of Celts.

Iceland has one of the smallest gene pools in the world – primarily a Nordic-Irish mix of about 300,000 people in a country barely more than a millennium old, first inhabited by Vikings who stopped off in Ireland on their way to Greenland and Newfoundland taking their pick of Irish slaves and serfs (a.k.a. thralls) with them. Hence the predominance of Iron Age Thors and pixie-like maidens on the streets of Reykjavik.

One also thinks of music and of course rain, which possibly explains the Celtic love of music, spurned on by convivial indoor get-togethers (a.k.a. sessions) to escape the colder and wetter climes of north-western Europe. There are few better ways to spend a misty winter evening than by a corner fire with a beer and a song. For those who can’t sing, the pints help loosen the vocal chords.

In Dublin, one can find a session most nights, from the famed O’Donoghues on Baggot Street, home of Luke Kelly, Ronny Drew, and the Dubliners, to regular fiddlers in The Cobblestone and Hughes. “Trad” music abounds throughout Ireland, including Leo’s Tavern near Crolly in County Donegal, noted as “the birthplace of Enya, Clannad, and Moya Brennan.” Clannad did the music for Robin of Sherwood – Robin Hood is an inspiring legend, but alas he was no Celtic warrior. Traditional Irish dancing is also popular and now world-renowned thanks to a 1994 Eurovision Interval Act called Riverdance, a thumping Celtic phenomenon starring Irish-Americans Jean Butler and Michael Flatley.

In Scotland, the cèilidh (or caile) is central to Celtic fun and a regular feature after a Highland Games competition. I had the honour of competing in one such games on the Isle of Arran off the Ayrshire coast in western Scotland, managing to toss a 80-kg, 20-foot caber almost 18 inches. Fortunately, I was better at dancing, learned in part through rural Canadian folk or square dancing – there’s nothing like the sweat of a rigorous dosey-doe or a grand chain.

The popular Highland Games features piping, drumming, Scottish athletics, and other staples of Celtic culture. One of the highlights of the Edinburgh Festival is the “military tattoo” with a wide range of pipe and drum bands from around the world, many in tartan clan colours (Check out Slanj Kilts for the best selection of traditional and modern tartan dress).

In Wales, the Eisteddfod pays homage to Welsh language and culture and their proud Celtic past. The week-long “sitting” features music, poetry, and readings in Welsh to honour the bard. On a cycling trip from Dublin to Port Merrion, I was surprised to be addressed in Welsh at my first stop. It’s a working language in much of northern Wales. Iechyd Da (cheers in Welsh) a.k.a. slainte in Irish and slanj in Scottish!

Of course, the bagpipe especially marks a Celtic heritage, a national instrument in Scotland (if such things exist), as Scottish as haggis or thistle. In Ireland, they’re called the uilleann pipes and in northern Spain gaita (gaitero is piper). They are all played slightly differently and, of course, the piper’s hat is also unique. Marching while playing is popular in Scotland (left), northern Ireland, and northern Spain (right).

A love of stories and fun (or craic as it’s known in Ireland) is also a Celtic trait, though one needn’t go as far as Judge John M. Woolsey, who in his landmark 1933 ruling that permited the sale of Ulysses in the United States after it was banned for supposed pornographic intent, said “In respect of the recurrent emergence of the theme of sex in the minds of [Joyce’s] characters, it must always be remembered that his locale was Celtic and his season Spring.” Makes it sound like the Irish maypole was code for an orgy, although it must be noted that the courser words in Ulysses were of Anglo-Saxon origin.

There are numerous pan-Celtic myths, many transplanted from older Norse, Roman, or Greek variations. The hero Lugh features prominently – in Irish, Lugh Lámhfhada (Lugh of the Long Arm) and in Welsh, Lleu Llaw Gyffes (Lleu of the Skillful Hand) – and is associated with the god Mercury. The most important Celtic goddess is Brigid (the exalted one), associated with sacred flames and healing wells. Later Christian traditions were superimposed on Celtic traditions, where Brigid has morphed into St. Brigid of Kildare.

The four seasons are called Imbolc, Beltane, Lughnasadh and Samhain, starting not on the astronomical markers of spring, summer, autumn, and winter as we know them, but at the midpoints; thus, Imbolc (February 1), Beltane (May 1), Lughnasadh (August 1), and Samhain (November 1). The Celtic mid-season dates may result from a more temperate climate and explain the greater importance of celebrations on May 1 (mid-point between March 21 and June 21) and Halloween (the day before Samhain). Imbolc is also connected to St. Brigid, whose feast day is February 1.

The Beltaine fire festival in Edinburgh atop Calton Hill is a bucket-list night out, marking the Celtic beginning of summer on May 1, and includes midnight bonfires and fertility-rights re-enactments with the May Queen, with plenty of lusty audience participation. Dancing at Lughnasa, a play by Derry writer Brian Friel (and made into a movie starring Meryl Streep), takes place around the Celtic harvest festival on August 1. A mix of Celtic, Christian, and pagan culture is put through the paces.

Spain has a lot of catching up to popularise its Celtic past, but it’s clear from the music that there is a common heritage – Asturian and Galician bagpipes and dress show a strong Celtic connection. As does the love of fun, drink, and singing. And there’s always el Celta de Vigo, though the C here is a th sound as in [Th]elta de Vigo. But as noted in “Galicia and Asturias: Celtic Nations with Celtic Heritage!” it’s not just language that makes one a Celt!

Great post, John, as always 🙂 Really interesting to know about our common heritage

Muchas gracias Paloma. It was great fun learning how connected we all are. Seguramente, todos somos primos. Slainte-Saludos.

Celtic culture alive and well here in the north and there are several inter celtic festivals to prove it, aviles, candas every summer gather bands of celtic dancers bagpipers etc and have a great ol time.

Thanks Terri. Indeed, I am just starting to learn about Spanish Celitc culture. Here are the websites for Aviles (in Spanish) and Candas (in English) for anyone who’s interested:

Candas and

Aviles.

If you are interested in Celtic survivals in NW Iberia, maybe you might enjoy reading this Quora answer:

https://www.quora.com/What-aspects-of-Celtic-culture-and-language-are-found-in-contemporary-France-Brittany-and-Spain-Galicia/answer/Jimmy-Miller-25

Also, a fascinating article about the connections between modern Asturian legends and ancient Irish sagas:

https://www.academia.edu/15921579/T%C3%A1in_B%C3%B3_Cu%C3%A1ilnge_and_Asturian_Oral_Tradition_Celtic_Survivals_in_the_Iberian_Peninsula

Let me know if they were worth it!

Gracias Cristobo. Great info! Lots to learn about the many shared cultural connections. I am also fascinated about the similar coastlines. I know they were connected eons ago, but parts of northern Spain and the west of Scotland and Ireland are almost identical. Twinned in so many ways! Xuanin

My grandparents came from the Asturias and I was surprised to learn that their musicians played bagpipes. I have a great attraction to all things Scottish, including the accent, and I wonder if there isn’t some Scottish DNA in my blood. Who knows? I’d like to find out more about the Asturias-Scotland connection.

Hola Ceci, Yes, plenty of similarities between Scots and Asturians: jovial, generous, kind, love of food/drink, and of course the bagpipes and funny clothes. The DNA is shared too if you go back far enough to include early continental migration. But I’ll take Scottish whisky over Asturian oruja. Me gusta pero muy fuerte. Xuan

Im Argentinian of Asturian, Galician and Irish heritage…

Love this article.

Hope to visit Ireland after the pandemia…

Regards from Buenos Aires