Bilbao’s old cathedral is in the heart of its medieval pedestrian centre (Siete Calles or Seven Streets), mostly forgotten today amidst the bonhomie of pintxo bars, but fortunately there’s a new cathedral in town, the Guggenheim, a shiny titanium-clad museum built in 1997 at the bend of the Nervión river by Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry. The Guggenheim has successfully transformed the once industrial Bilbao into a tourist Mecca. Prior to 1997, there were 25,000 visitors a year. In the first three years of the Guggenheim alone, more than 4 million tourists came.

The awe inspiring new cathedral comes complete with altar pieces dotted round the exterior, most notably a sublime 43-foot-high flowered dog, clothed in an array of blooms that are kept fresh with regular changes throughout the year. Puppy, by American artist Jeff Koons, acts as a quiet guard dog ushering in the unwashed through a rather nondescript museum entrance. On the more impressive river side, three much-larger-than-life sculptures mark out this cathedral as something special: Louise Bourgeois’s giant spider Maman (1999), Jeff Koons’s coloured steel Tulips (2004), and Anish Kapoor’s shiny steel Tall Tree & The Eye (2009).

Bourgeois’s giant Maman is truly scary while Tall Tree & The Eye, a collection of 73 stainless steel reflective spheres, shimmers beyond reach of its tentacle legs. Designated as “scientific rationalism” and a “dynamic interplay of light,” Kapoor’s circular modern cross shines with hope next to the clutches of the devil spider. We, the viewers, as always are caught in between.

Of course, the real art is the Guggenheim itself, an exquisite abstract sculpture ship, praised by some as the most important building of the twentieth century. Built by licence through the Guggenheim Foundation (after Solomon in New York and Penny in Venice) for $89 million, the Bilbao version reportedly paid for itself after only five years. Not bad to remake a lost industrial city of almost 1 million. As Gehry noted when he received the 2014 Prince of Asturias award for arts, “Bilbao’s business model was amazing” (Frank O. Gehry Architect – Royal or Rebel?).

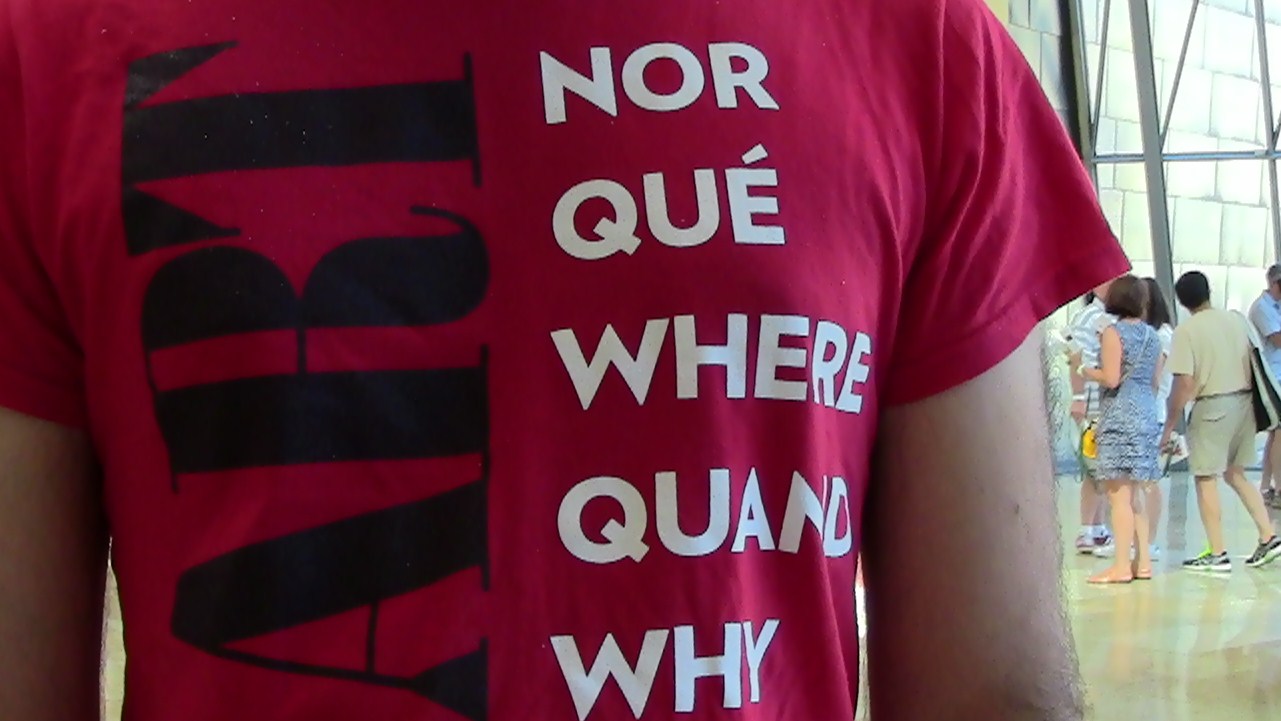

More Gehry than Guggenheim, it has always been difficult to install sufficiently iconic art within its massive interior. This summer, exhibitions by Koons and New York street artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (a.k.a., Son of Warhol) try to expand the art to monument, along with the permanently displayed works of Richard Serra and Jenny Holzer. Love him or loathe him, Koons is one artist whose works can fit the scale required of the mammoth container. The more traditional stuff just gets lost in the massiveness.

The €15 entrance cost includes a non-optional audio guide, turning the gallery experience into an intellectual tour rather than a usual do-what-you-want sashay through the local hall of fame of past masters. With audio guide in hand, one happily partakes of the ordered 3D walking tour, to be sure an improvement over lonelier unguided visits. Alternately narrated by a posh British man and a spirited American woman, we are told that the “ah-trium” is the heart, pumping people through the arteries of Gehry’s self-styled “free-associated building.” The titanium exterior was computer designed and the smooth limestone interior tiles created by an automated robotic system. It takes little effort to see that the art inside has been similarly constructed.

The highlight of the permanent collection is Richard Serra’s The Matter of Time (2005), 20 massive rusted steel “shapes,” leaning elliptical sculptures that snake along most of the ground floor in a dedicated room (The Fish Gallery), aptly sponsored by the giant steel company Arcelor. The 14-foot-high pieces are truly monumental, brutally simplistic, perhaps the only kind of art that can compete with the building itself, like primitive hedge mazes arranged in perfect leaning balance, defying gravity. Inside, one is subsumed by optical illusions and falling feelings, as the statues of secular saints prod us to thoughts about creation. A video shows the exacting task of creating, transporting (truck, ship, crane), and installing the mammoth works.

In reality, Serra’s sculptures are interactive play things, an extension of the building itself enjoyed by the hundreds walking through – touching, clapping, snapping – although one is technically forbidden to interact too closely, according to the prominently displayed communion rules: no touching, no photos, no sacrilegious remarks. It’s a majestically playful adult playground for the modern adherent, releasing one from an overly structured world. New interactive secular play, ever disorientating, almost ecstatic, a quest through the maze of ideas as if to a supposed end.

Control seems to be the recurring theme throughout our stage-managed interaction. In Jeff Koons: A Retrospective (June 9 – September 27), viewers are instructed upon entry that “Photos (without flash) for private, non-commercial use are exceptionally allowed in the marked spots.” The “marked spots” were indicated on the floor with a camera icon and PHOTOSPOT text, art in itself if you want to think postmodern, though there were only four such marked spots over ten rooms and two floors – in front of Lobster, Popeye, Balloon Dog (Red), and Michael Jackson and Bubbles (all of which would cost a cool €250 millionish if you so desired to own them).

Each marked spot had an accompanying partner “stand spot” indicated by a pair of shoes icon, presumably to include selected friends in a choreographed peripheral position, like a clingy medieval cherub, but were so peripheral it was difficult to arrange object and friend in the same shot.

A thoughtful attempt to include the viewer in the art? More like reemphasizing that we are the outsiders straining to play with the big boys. An afterthought essentially. Interact only as commanded. One can’t allow any old interaction as in the poor 12-year-old boy who put a hole in a €1.3 million painting after tripping at a Taiwanese museum. Tsk tsk.

On the accompanying audio guide, Koons’s creativity is said to be “without ego,” though one wonders how such self-consciously created objects can be egoless. Irony is the height of ego. It is nonetheless amusing to browse through room after room of big iconic stuff in a gallery that was made for big iconic stuff.

Indeed, to understand Koons is to understand big. His larger-than-life sculptures poke fun with convention, alas itself rather conventional after too much of the same. He makes small big, rough smooth, ugly pretty, but tries too hard to control the user’s interaction, almost anal as he attempts to program our interactive selfies and to limit our fun. Only four PHOTOSPOTS? Is he saying there aren’t enough utilitarian objects to go round?

He even supposes to think big, noting that “For me the stainless steel is the material of the proletariat, it’s what pots and pans are made of.” I never imagined myself as a proletariat or that pots and pans were so easy to work with. Further on he adds, “It’s a very hard material and it’s fake luxury.” Indeed, there is a lot of fake luxury in this retrospective. Unaffordable to all but the richest collectors of Pop (or Blow-Up) Art. He ought to have heeded Picasso’s advice: “Copy anyone but don’t copy yourself.” Of course, easier said than done when one has a winning formula for creative commercial success.

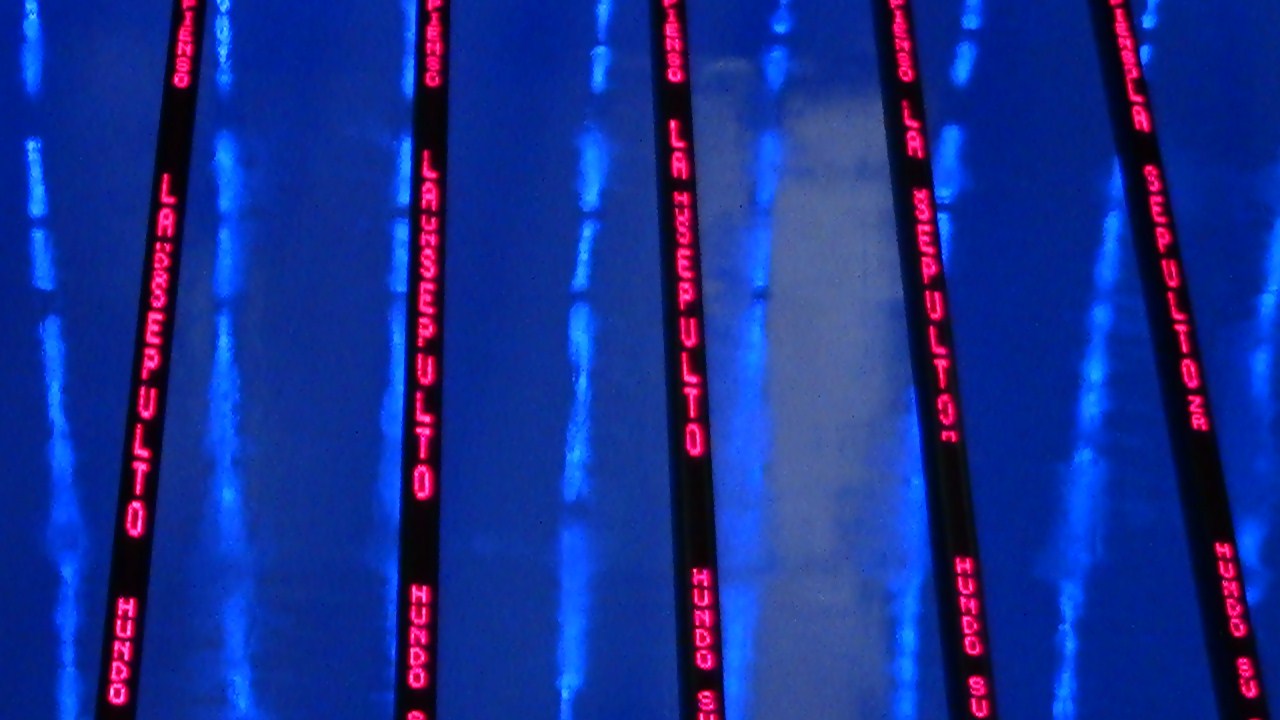

My favourite piece is Jenny Holzer’s Installation for Bilbao (1999). Her work has always fascinated me, and her magnificent 9-column, running-LED display (up and down in blue and red) mesmerizes as text appears and disappears from floor and ceiling. Words race up and down in a myriad of languages, inviting one to ask where creation comes from. It is monumental like all the others, but accessible all the same.

To be sure, the Guggenheim is impressive, and easily dwarfs other modern art galleries. All the more since we no longer go to church, but to large cathedral-housed galleries to commune with our better selves. The Guggenheim is a shape, “a confluence of juxtaposed shapes” we are told. According to Gehry, “I’ve always thought of the city in sculptural terms. The city is a sculpture itself.” And now, with a modern cathedral where one comes to be a part of a new secular, it’s a shape you walk into like a playground with swings and teeter-totters. The building is the show.

If one isn’t into large playground art, there is more on offer in Bilbao. One can happily amble along the gentle beauty of the remodelled Nervión river promenade and let the midday breeze blissfully blow past.

Or check out the pintxos bar in the oldest part of town, wall-to-wall eating in a peaceful pedestrian centre. Just meander through the narrow old cathedral streets, and take in the gastronomic delights on offer at hundreds of different bars. Indeed, Bilbao is home to the pintxo walk (or pincho in Spanish), dreamy hors d’oeuvre washed down with wine or beer, though more like a meal after 5 or 6. One gets lost in time and space in search of the perfect pintxo creation.

Prices vary, so watch out for the engaños (rip-offs) like Berton, an attractive but ridiculously priced pintxo trap. We had their “medallones de solomillo y foie” for €3.50, which alas came with a withered slice of pepper, a miniscule sliver of foie (on the side), a damp cut of bad bread, and only ONE medallion. My Spanish is an ongoing process, but I know my plurals – medallones suggests at least two!

Clearly Bilbao is enjoying its makeover tourist status to reel in the unsuspecting. For a great menu del día though, after the requisite pilgrimage to the Guggenheim, I recommend the nearby Larruzz Bilbao on the river side. You won’t feel you splurged as you recount the monumental.

Best of the “pinchoterías” (my first coined Spanish word) was Santamaria, where we had a delicious bacalao (cod), melted cheese, and jam creation. Better yet, take a quick trip to Portugalete for even cheaper pintxos (a half hour, €3.20 return ride on the metro) at the mouth of the Nervión with its World Heritage Site Puente Vizcaya, the oldest hanging transporter bridge in the world. If you take the bridge (€0.70 return) you can check out the beaches of Getxo in the really posh part of town.

Even better (if you’re after good fairly priced pinchos), try Castro Urdiales and its “ruta de los pinchos” in nearby Cantabria, that is if you’re flying from Santander. Here, one gets pinchos galore for a euro each in any of a dozen coastal pinchoterías. Meson Marinero was the best of a great bunch. No iconic modern cathedrals to jack up the prices, just simple tranquillity on the edge of a quiet ocean. Of course, pinchos like art is subjective, but I’m sure you’ll love it.

To be sure, everyone is a critic these days, so I have an idea for the Guggenheim if it really wants to offer a new cathedral experience, a modern communion for today’s adherent: the “Selfie Box.” At the outside entrance, one stands on a marked PHOTOSPOT, smiles (or mugs), and the image is instantly transferred to a video wall containing hundreds of other similar selfies. Just think how much fun to see ourselves on gridded display, to be part of the art, to be instantly artized.

How could one not ponder one’s place, or the line between artist and viewer, priest and believer? But then we might not care so much about the real professional art on the real professional walls.

The guiri sure gets around. Glad Bilbao entertained and gastroed you well!

Thanks Terri. Have hat will travel! Bilbao is a great place to enjoy art and food. I was happy to go on the necessary pintxo walk — the Spanish pub crawl. Esto es vida.

After the dramatic industrial crisis of the 1980s, Bilbao was forced to rethink its very economic foundations. That is how it transformed into a successful service town.

Yes indeed a very good point. Rebranded, reinvented, and reinvigorated. Bilbao is the model for remaking an old industrial city. I would like to see a few new ideas inside the Guggenheim as well as out. Onwards to more.