In the art world, few cities rival Madrid with its three world-class galleries: The Prado, The Reina Sofía, and The Thyssen. There’s the National Gallery in London where one can gaze for free at Van Gogh’s Sunflowers or Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières in less than 30 seconds from the steps of Trafalgar Square, the MOMA in New York which while not free is within most budgets and has many of the best French Impressionists, and the exquisite Van Gogh Museum or recently refurbished Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, which is full of the best of old and new Dutch Masters including Rembrandt’s famous Night Watch. The Louvre, well, you need the patience of Job to get in.

My favourite of the Spanish painters is Goya. Anyone who changes from court painter to chronicler of the folly of war, the madness of Napoleon, and the excesses of the French Revolution is in a class by himself. Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) started out making paintings for King Carlos III and then King Carlos IV, enjoying the best of patronage and privilege. Somewhere after Napoleon changed from inspired corporal to deranged emperor and invaded Spain in the so-called Peninsular War (1807-1814), Goya grew a conscience. In the end he went a bit crazy exploring the depth of his dreams in a series of eerie Black Paintings that prefigure the Expressionists.

The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808 are his crowning glories – floor to ceiling paintings that hang side by side in El Prado – depicting two events between Napoleon’s army and the citizens of Madrid. The first shows Madrileños resisting the marauding French troops and the second the resisters being executed the next day by a retaliatory French firing squad. The size of the paintings alone if not the overreaction by the French sends a chill down your spine.

In The Prado, one also finds Goya’s two majas: La maja desnuda (1800) and La maja vestida (1803). La maja desnuda certainly upset a few old church types, and her bold gaze changed the way we look at (and are looked at by) nude portraits. Contrast Goya’s maja with Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus a.k.a. The Toilet of Venus (1651) in London’s National Gallery and her shyer indirect gaze.

More triumphant for Velázquez is his famous Las Meninas (1656) also at the Prado, showing the playful painter off to the left presumably painting the painting itself. Various levels of games within games and competing vantage points including a mirrored king and queen watching their daughter give Las Meninas its enigmatic beauty. Menina means young girl in Portuguese but has become known in Spanish as the maids who attend royalty. Are we all play things for our royal masters?

For the Spanish Master class in war horror, one has only to walk a few blocks from El Prado to The Reina Sofía and Picasso’s Guernica. Again, the sheer size alone is mind-blowing and the horror mesmerizing. Guernica is the pre-eminent modern painting and sadly defines a modern world permanently at war with itself.

As Gijs van Hensbergen wrote in his fascinating Guernica: The Biography of a Twentieth-Century Icon: “It has never lost its relevance, nor its magnetic, almost haunting appeal. From its first showing in Paris to its arrival in Spain forty-four years later, it has witnessed and helped to define a century. That its lessons have still not been heeded or learnt makes it as relevant and iconic today as it ever was. Guernica, for better or for worse, more than any other image in history has helped to shape the way that we see.”

Run, don’t walk, to see it. Whether it should be in Madrid or in the Basque Country (say, for example, in the fabulously designed Guggenheim in Bilbao) continues its modern story. There are of course other Picassos to be seen in Madrid. After many years of trying I think I am finally finding a way to appreciate the extraordinary volume of his work.

Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) was born in Catalonia and has always inspired one to think underneath the simple surface of living, or at least to question our senses. Not easy to do with paint and canvas. He is one of the leading Surrealists along with René Magritte. If your tastes are more classical, there are a few of his pre-Surrealist works on display at The Reina Sofía, including the simple and tranquil Figura en una ventana (1929). An everyday woman looks out an everyday window at a scene of resounding calm.

Oddly, the largest Dalí collection in the world (The Dalí Museum) is in a small St. Petersburg, Florida, suburb. Turn left as you pass over the Gandy Bridge from Tampa just before the girl in the electric pink bikini selling beer on the side of the road. Dalí would be amused. The reason for so many Dalís in St. Petersburg, of all places? In 1942, millionaire mining businessman Albert Morse and his wife Eleanor became fascinated by his work after seeing a retrospective at the Cleveland Museum of Art. A year later they bought their first Dalí – Daddy Longlegs of the Evening, Hope! (1940) – and didn’t stop.

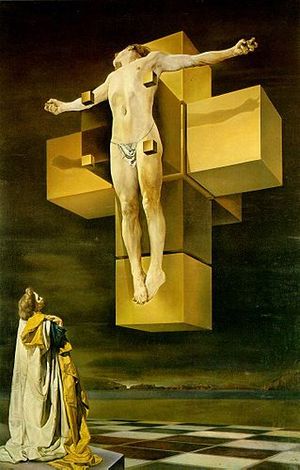

Most think of The Persistence of Memory (1931) or The Disintegration of Persistence of Memory (1954) and the relativistic time-warping clocks when they think of Dalí, but I think of Cruxifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) (1954) as his masterwork. A three-dimensional cross for a three-dimensional Jesus seems more appropriate to understand the mysteries of our ephemeral spiritual world, and suggests more than a drab death. On loan for 20 years in St. Petersburg when I first saw it (while helping to launch small rockets off the Gandy Bridge), Cruxifixion is back at MOMA.

Another favourite is The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus (1954), showing a white-robed Columbus about to step triumphantly onto land (presumably modern-day Cuba). For Dalí, this symbolized his own journey to America where he found his fame and fortune, and also pays tribute to a Columbus who at the time was believed to be from Catalonia not Italy. Dalí can be seen as a monk in the foreground.

Well, that’s just the tip of the Spanish art iceberg. And I haven’t exited the two main Madrid galleries, included sculpture, film, or architecture, or made it to the twenty-first century. As for the fiesta side of life (number five on my original top-ten list), obviously much more research is needed.

For more on prices, times, and the latest exhibits in the main three Madrid galleries, check out El Prado, The Reina Sofía, and The Thyssen. There is a reduced three-museum ticket available at any of the three.